A Voyage of Seemingly Propulsive Speed and an Apparent Absolute Stillnes

Co-written by, Arshad Hakim, Moonis Ahmad Shah & Sarasija Subramanian

In a conversation, a friend once said, in literature, we have only two frameworks through which we narrate our stories; through journeys and through tragedies. We mark life through these narrative modes; through journeys and tragedies – psychic, emotional, social, and political. Three words resonated while we thought of this show: Myth, Suspension, Violence. While thinking through these we thought of language and how language fabricates worlds, and through language, we thought of context.

Myth, a widely held, but ‘false’ belief or idea. Defined as beliefs and ideas that are ‘false’, narrated ‘colourfully’ to talk about happenings outside of human understanding, or stories that exist outside of scientific study or laws of nature. A myth, within this framework, questions the concept of what is ‘outside’, and lays down a parallel set of truths; a metaphor, a tangent, a parallel, an expansion. From a different lens, myth could also be seen as social speech, one that governs a group of people in order to form narratives that become associative and thereby affective, largely functioning in binaries of good versus evil. To use a myth is to engage with the performative, as myth is performance. This is also to say, that by engaging with the myth, one engages with the various kinds of imaginaries that the myth embodies and unfurls them. In doing so, one performs the myth by becoming one of the entities that engage with it and then pass it on—sometimes as it was, sometimes altered.

Suspension, as a categorical frame, is a condition where time and space, and their perception is out of joint. Social, political, psychological, inebriated states that lead to refracted conceptions of time and space, are states of suspension. Think: you’re constantly looking at everything through a prism, it is beautiful but it is messing with you. A suspended state is also a state of fragments, that are out of joint and are never placed in a whole. Everything seems magnified, blurred, you cannot make out what is what—and then this becomes a state of living life. We perceive space and time through the language we use. As language functions in a linear manner, our perception of temporal and spatial relations are bound by this linearity in how we experience them. Everything outside of this feels suspended—outside the ordinary, or the known. This lack of linearity can link itself back in parts to time and space being magnified, reduced, or overlooked.

Violence is constitutive of human nature and must be contextualized in order to be understood. With each passing step, the ‘normal’ (extended to the idea of the self, or us) attempts to breakdown and communicate with the ‘abnormal’ (the other or the object we see outside of the self) by using a language that is our own. This rift between the language of the abnormal and that of the normal raises questions of violence, as even in our well-intentioned fight for the lesser or the weaker (as we define them), two biases arise. The first, becomes the fact that we have separated ourselves from the other and taken it upon ourselves to protect it. The second becomes the mode of protection itself, which only separates us from it further. “The liberty of madness can be understood only from high in the fortress that holds madness prisoner. And there, madness possesses only the morose sum of its prison experiences, its mute experience of persecution, and we—we possess only its description as a man wanted.” – Michael Foucault, Cogito and the History of Madness.1 One never thinks of what violence is while it occurs. In that light, the focus is not on forming frameworks of what violence is, or what violence does, but it is rather to see what the residues of violence are. In any form of violence, the residue is always fear, and fear is paralyzing.

Within stagecraft, a common method that is used to depict changing scenery is scene shifting—a method of showing a change in the locale of the play. Within proscenium theatre, this would be a way to change flats (in theatre, flats is a term that is used to denote realistically painted backgrounds), moving them forwards and backwards to change the setting. As a more evolved version of scene shifting, came a revolving stage. This theatrical device uses a turntable around a central pivot and is revolved before an audience. A background would provide the audience with information as to where the scene is occurring, and this information would be crucial in understanding the finer modalities of the play. To think of context is to think in terms of volatility. To think that the position which is undertaken is susceptible to change and is constantly morphing. A position towards a thing is never an apriori, it is rather a negotiation. To think about context then is an exercise in mapping an ever-morphing negotiation.

________________________________________________________________________________________

Arshad Hakim – Orobours (2020), LED Running Strip, 96 x 12 inches

Arshad Hakim works around the idea of dislodged subjectivities, how they are formed and how they operate. He does so by often using pre-existing material and repurposes it to highlight shifts in reading/viewing, that incorporating various senses of embodiment. In Ouroboros, Arshad references two lines from Parajanov’s ‘The Color Of Pomegranates’; “You are fire. Your dress is fire. You are fire. Your dress is black. Which of these two fires can I endure?” He repurposes these lines to, “I am fire and my dress is made out of fire. I am fire and my dress is not black.” In doing so with text, that is part instructional and part descriptive, and which talks about desire and exhaustion in its cyclical nature, he in some ways answers Parajanov’s question of which fires one can endure. In shifting the context from which this text is taken and repurposing it in his work, he provides an alternate reading to the text, but in oblique ways also incorporates what Parajanov meant. What could be said about changing contexts, is that through its dislocation from the former context, there are new openings in which the said thing could be read and understood. This, in turn, would provide new spaces that one can access. Within Arshad’s work, he not only changes the contexts within which the reference initially functioned, but in the process he opens up psychic, emotional and political spaces that are absent in the original reference.

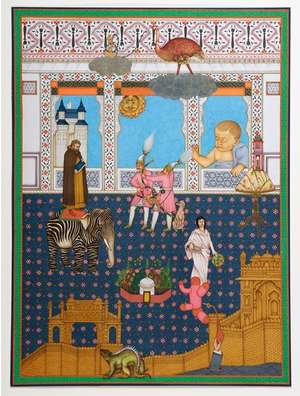

Moonis Ahmad Shah – Birds are coming (2017), UV Print and light box, 21 x 17 inches

Moonis Ahmad Shah – Using archival materials as references ranging from text, mass media, and cinema to historical documents, Moonis Ahmad aims to establish an interdisciplinary art practice, which on one side uses archival material from the past and on the other, uses newer technologies and programming languages, to question the archive’s constitution, boundaries and materiality. In the Birds Are Coming, Moonis curates an archive of birds accused of espionage by various nations. The installation, in the form of light boxes and an interactive web archive, curates their last known photographs, mugshots, and investigation archives. These, as claimed in the work, are “stolen from the authorities who were responsible for investigating their crimes”. The archive itself builds upon a story—one whose credibility is upto the viewer to decide—and allows with it a reading of violence, which is rooted not in the images we see in our day to day, but instead in an alternative. The work’s context then lies not within its own fictional history, but instead within our perceptions, understanding and experience of violence as viewers, and its consequent illogicality from time to time.

Sarasija Subramanian – Dictionary of Gardening, Bedding 1 (2020), Etched drawings on zinc plates,13 x 10 inches

Sarasija Subramanian’s practice stems from analogies derived from the organic world in relation to its cultural and political implications. In the process of research, interaction and documentation, her active archive of images and objects continues to grow and incorporate multiple histories and presents. In Sarasija’s work, The Dictionary of Gardening, pages from a series of books (published in 1887 in London) are extracted, and reproduced onto etching plates as drawings and transfers. In reproducing specific pages of the book—one that was originally produced using metal plate engravings and a letterpress—she brings back the information, tracing parallel processes and materials, allowing her to recontextualize what is being said. The act of reproduction, in this case one that is either re-drawn by hand or edited and reduced to excerpts, creates a tension between what is ‘true’, and what has been altered, or fabricated. Constantly questioning the factual nature of what is being represented or instructed opens up with the work multiple possibilities of reading, while the excerpts of text that have been reproduced bring in to focus how language, when isolated from its context, creates new meaning.

“The object really does become the other, because we have made it so. We manufacture realities. We use the raw materials we always used but the form lent it by art effectively prevents it from remaining the same. A table made out of pinewood is a pine tree but it is also a table. We sit down at the table, not at the pinetree. Although love is a sexual instinct, we do not love with that instinct, rather we presuppose the existence of another feeling, and that presupposition is, effectively, another feeling.” – Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet.²

Endnotes:

1. Michael Foucault quoted by Jacques Derrida, in Cogito and the History of Madness.

2. Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet, Penguin Classics,1982.

References:

1. Bruce B. Lawrence and Aisha Karim, Violence: A Reader, Duke University Press, 2007.

2. Roland Barthes, Mythologies, RHUK Revised Edition, 2009.

3. Title text from Sarasija Subramanian’s ‘As she rises and falls – in conversation with Lucy Irigaray’, referencing Lucy Irigaray’s Marine Lover of Friedrich Nietzsche.