The Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2018

Written by Nupur Dalmia, February 5, 2019

A few of us at Gallery Ark had the pleasure of visiting the Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2019 with Indrapramit Roy, who is a practicing artist, an Associate Professor of painting and the Dean of students at the Maharaja Sayajirao University in Vadodara. He studied printmaking in Shantiniketan and subsequently painting at MSU Vadodara. He was awarded Inlaks Scholarship to study MA Painting (1990-92) at the Royal College of Art, London, which included a term at Cite des Arts, Paris. He also spent a term at the Hochschule der Kunst, Berlin on an Erasmus Exchange Scholarship. He has been shown widely nationally and internationally.

More importantly, Indro Sir is an exceedingly patient teacher who is truly happy to take anyone under his wing. Our Biennale experience was greatly enhanced by his company, his sheer energy and curiosity to take in as much as possible, his uninhibited manner of answering questions and imparting his vast knowledge on just about anything in the art field. We have therefore chosen to chronicle our journey by way of an interview with Prof. Indrapramit Roy, paraphrased by Nupur Dalmia.

What is the purpose of a Biennale?

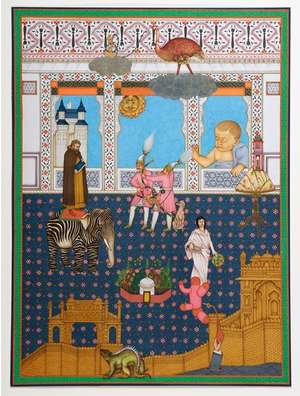

The idea of a Biennale is to bring together the ‘best’ of contemporary art from across the world, but it is naturally colored by vision of each curator. The Biennale means to look closely at how art is evolving. Consider tribal art for instance, which by definition, is rooted in cultural and religious motifs of a region. There is a contemporary happening here too. Santosh Kumar Das from Delhi works within the framework of Madhubani painting but instead of portraying the traditional Krishna myths, his work is extremely political or intently personal. Durgabai Vyam and her husband, featured in this Biennale, are also trying to push the scope of folk art. Hybridity makes art alive, as it does cultures. ‘Pure’ art or culture is a myth and evolution is essential for its relevance. New words added to a language are proof that it is living. Similarly, art looks to outside cultures and prevailing vocabularies to absorb new elements. However, not all artists experiment.

Unlike other shows, the Biennale is spread over a large span of three months. Art is displayed in makeshift venues that are not specifically designed for this purpose. Therefore, the curatorial challenge is to find appropriate homes for works of all sizes, natures and mediums, in a manner that harmoniously comes together.

Can you describe Anita Dube’s curatorial intent and its execution?

Anita is well known for making political statements through art. As part of the Radical Group, she comes from an outré, slightly anti establishment, school of thought. Contemporary art often takes that position in its effort to look at alternative practices beyond painting, sculpture, printmaking. This energy is most obviously reflected in the works of Chittaprosad, Krishnakumar, BV Doshi, and Shilpa Gupta, but most others also touch upon relevant social and political themes.

Her focus seems to lie on introducing people outside the art fraternity to contemporary art. To that effect, she has included several works that are not necessarily new but are arguably the most noteworthy works of an artist – works that one might be familiar with in theory. I see merit in her strategy because, William Kentridge’s video installation for instance, creates vastly different experiences when seen in person as opposed to when seen on YouTube. Perhaps then, the curatorial intent is slightly didactic in its consideration for teaching the audience. It places importance on artists working with pertinent issues through alternative mediums and/or practices vis a vis artists creating experiential works. Some salient issues include the recent Kerala floods, the state of feminism in India, the environment, politics, and more. This also happens to be an international art trend at the moment.

There is more subjectivity involved in this genre. Two individuals will always react differently to a work of art, but if the work is commenting on a social issue, its perception will also be colored by a viewer’s opinion and experience of that issue. A degree of background knowledge about the artist and the work becomes essential to properly understand such works and therefore, the viewers’ discipline has a huge bearing on the curatorial efficacy.

Given the didactic intent, I wonder if the Biennale provides an equally rich experience for a professor like yourself as compared to a newcomer?

Perhaps not. Although the wall texts provide some background, they cannot substitute a long term familiarity with an artist’s work. But this is not an apples-to-apples comparison. Good art will always have appeal across the board because it is nuanced. It is not necessary to catch all the nuances – a few are evident at face value and each one is likely to be revelation enough.

Good children’s literature is a fitting analogy. It is read and re-read by children and adults alike, simply because there are new discoveries to be made each time in the subtext. Consider for instance, Alice in Wonderland. A child is most interested in the story, the fantasy of it, whereas an adult might wonder where the story comes from, whether it reflects life. Their experiences are different but both impactful in their own right, much like good art. When I look back at my Biennale experience, some works come to mind first, some will even stay with me forever because they have moved me fundamentally. All good art will have an undeniable impact in varying and subjective degrees.

What are some noteworthy works this year, that are a must-see in limited time?

The Aspinwall (ft. Anju Dodiya, Song Dong, Martha Rosler, etc), Pepper House (ft. Lubna Chowdhary, and Heri Dono)and the Durbar hall (ft. Mrinalini Mukherjee, Chittaprosad, and KP Krishnakumar) are must-see venues.

William Kentridge and Heri Dono were the biggest highlights for me this time. They both use a certain levity and are transversed with surprising elements of humor. While they are enjoyable as they are, they reveal interesting perspectives on the tragic apartheid in South Africa and long history of colonization in Indonesia.

There were several works with interesting subtleties. A few that immediately come to mind are, the experiment by Oorali Express, Bapi Das’s embroidered autorickshaws, Sue Williamson’s One Hundred and Nineteen Deeds of Sale, Martha Rosler’s collages with magazine illustrations of a middle-class existence during wartime called House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, EB Itso’s photographs, Cyrus Kabiru’s photographs, Lubna Chawdhary’s Metropolis, Gargi & Veer Munshi in the Kashmir Pavillion, the immensly moving work by Chittaprosad in Durbar Hall, Kaushik Mukopadhyay’s Small, Medium but not Large, photographs of Giles klark and Nick Ut, the Guerilla Girls were fun, I got to see Krishakumar’s drawings after a very long time, and lastly after having seen her large solo, Mrinalini Mukherjee’s work was very interesting in this context.

Some interesting videos besides Kentridge were Song Dong’s Touching my Fathervideo, and Kobenhavn Hby EB Itso & Adam Kraft, a film about living on the fringe of society in a hideaway on railway tracks, was moving in the parts that depended on visuals. The rest of it felt like a documentary; I wish it said a little less. Sanna Irshad Mattoo’s video in the kashmir pavilion about a gravedigger sharing his misery was also interesting. He narrates stories of a grave being dug repeatedly for different sets of visitors looking for a relative, but they are all faced with disappointment. He talks in a matter of factly manner but also sounds very emotional. Finally, it ends with him saying ‘no let them rest’. While this has a strong documentary feel to it as well, the man’s face and its changing emotions give the impression of animated black and white photos.

Were there any works that particularly disappointed you?

I did not particularly like the film on Shantiniketan by the Otolith Group. If the intention was to promote Shantiniketan or educate the world about it, as someone who knows the place well, I do not think it was accurately portrayed. The drone photographs and snippets of culture felt rather gimmicky.

One would expect Jun Ngyuen Hatsushiba’s video Towards the Complex-For the Courageous, the Curious, and the Cowards, of pulling a rickshaw underwater to be more immersive. While it was interesting, the physical experience of wading through water did not add much to the viewers experience. Last year that space had a work by Raul Zurita calledThe Sea of Pain, which also required viewers to walk through water. In contrast, my experience of Zurita’s work was so moving that it was difficult to hold back tears. Unfortunately, it is impossible not to compare works with those from previous editions, especially ones that share similar elements or the display venue.

Speaking of videos, there were quite a few of those in this edition. How does this affect the biennale as a whole? Does it give too much weightage to one medium relative to others? What are your thoughts on the videos?

Indeed, it felt like this edition was celebrating video as a medium but the other forms and mediums were also represented significantly if not equally. The idea is to display works that best fit Anita’s curatorial scheme. Having said that, as a painter myself, I do wish there were more painterly works. There were not too many of those with some great exceptions like Nilima Sheikh.

In light of some mixed opinions around the videos, it is important to consider that a video made by a painter or sculptor will have vastly different grammars than that of a filmmaker. For one, an artist’s video may not have a narrative at all. They are also likely to use time differently. An artist often uses videos to slow time down, to set his own pace for the viewer’s experience.

William Kentridge’s 8 panelled video art “More Sweetly Play The dance” is being talked about a lot. What makes it significant? – content, aesthetics, skill, concept?

The work is stunning in its visuality and its sheer power to hold you transfixed for multiple reruns, noticing something new each time. It was a very immersive experience with an intrinsic “Africanness” about it. Kentridge is from South Africa, and despite the country’s tormented recent past, the video is almost celebratory on the face of it. The dance, music, rhythm, and the drama of that entire vista creates a spectacle that is impossible to ignore – and I do not mean spectacle in the negative sense. The bits of shadow puppetry in the backdrop are especially interesting. It has references to other black artists, to William Kentridge’s own body of work, the American artist Cara Walker, as well as the general medium of stop motion animation with drawings and concurrent layers.

On one hand the video celebrates African culture and history, but on the other it is a funeral, reminiscent of the apartheid experience. Some cultures celebrate funerals, perhaps as the soul’s release from the circle of life and death and reincarnation. While it touches upon several such themes, none are made explicit. It evokes an elegiac note in the middle, with respect to life and the passage of time. There is a band with all its paraphernalia, but the viewer is left guessing the cause for celebration.

Shilpa Gupta’s (For in Your Tongue, I can not fit, 100 jailed poets) and BV Suresh’s (Canes of Wrath) installations also create a distinctly immersive environment. What did you think?

While I liked BV Suresh’s work I did not get to experience it as intended. I believe there was a technical malfunction in some sticks. He has created an enclosed dungeon-like space, and to that effect, maybe stouter Lathis with visible evidences of use would have worked better.

Shilpa’s work is rather immersive. The viewer is transported into a dramatic tomb with 100 works of poetry displayed on spikes. Unlike Kentridge’s video, the message here is singularly clear – ‘free speech‘ is the first enemy of an undemocratic spirit. The poets’ diversity of race and nationality is an extremely sad but weighty realization in itself. Making this work entailed huge research and I can only imagine how powerful this work would be if a viewer knew the history of every poet.

Finally, what makes the Kochi Biennale stand out from other art festivals and displays?

It stands out because it largely caters to the general masses. It does not try to whitewash reality or pretend to be something else. There is a strong heritage attached to some of the structures and Kochi’s natural beauty lends a wholesome quality to the atmosphere. It is truly comfortable in its skin and therefore the people have made it their own. There is deep engagement from people outside the art community. For instance, I met a young volunteer who is currently studying marine engineering. One does not often see such a diverse involvement.

Unlike most other art events, it is also refreshing to see that nobody is talking about money at the Biennale. Obviously money is involved and it is very important to sustain art, but here it is kept well in the background. You do not see people clamoring to buy certain works or any negotiations.